It’s been said that there’s great strength and power in community. At the Looking Glass Foundation, we definitely believe that. It’s with our bighearted community of people and organizations, that we truly can make a difference in the lives of others, in the lives of those fighting eating disorders. Together, we can move this disease from silence and isolation towards conversation and community.

One of these organizations is Sympli, a Canadian fashion manufacturer that feels we should all be accountable for holding women’s body image with kindness and respect. Sympli believes that everyone should be aware of their power to create an impact, and this shared belief is what brought Sympli and the Looking Glass Foundation together. Believing that "all women should love who they are without compromise", Sympli manufacturers an extensive line of flattering clothing that is is designed with purpose, and crafted with heart. They want women to wear clothes as a compliment to their individual personality, mood and purpose – and to dispel the myth that they would be happier with a 'perfect body'. Not only are they redefining how the fashion industry can make women feel good about themselves ... they are also showing women how to take back their power and create positive change. May the movement grow and flourish!

“Every single woman is beautiful and deserves to feel confident and comfortable in her own skin. Companies need to learn how to do business differently, they need to see that there is potential in standing up for what you believe in.” - Abbey Stimpson, Sympli Brand Manager

Anyone who's ever been to a Looking Glass Gala knows that Sympli donates generously to the Foundation, and has done so for many years. And they continue to amaze us with their support such as donating all of the proceeds from their upcoming 2-day Warehouse Sale to Looking Glass. We can't believe that it's been almost 10 years since this wonderful relationship with Sympli began.

Calling them "a source of passion, love, and unending support", Looking Glass co-founder Deborah Grimm recalls when Sympli first began supporting the Foundation. "They arrived on our doorstep out of the blue, embraced us and just never let us go", she says. "They have taught me so much about life and goodness, and I know I will never be able to truly express the depth of gratitude I feel for their trust and generosity."

Calling them "a source of passion, love, and unending support", Looking Glass co-founder Deborah Grimm recalls when Sympli first began supporting the Foundation. "They arrived on our doorstep out of the blue, embraced us and just never let us go", she says. "They have taught me so much about life and goodness, and I know I will never be able to truly express the depth of gratitude I feel for their trust and generosity."

The Looking Glass Board Chair, Debbie Slattery, echos the same gratitude. “Sympli has been a long-time supporter of the Looking Glass Foundation and we are deeply grateful for their commitment to raising awareness about the work we do and for creating the space for women to feel comfortable in their bodies."

Since 2009, Sympli has enabled Looking Glass to support hundreds of people, and their loved ones, dealing with this serious mental illness. Together, we can continue the dialogue around positive body image. Together, we can encourage every person to value themselves just as they are. Together, we can embrace those impacted by eating disorders and support individuals on their paths to recovery.

A big Thank you to the wonderful team at Sympli – for giving so much, and in so many ways.

Join us on November 22nd - 23rd for Sympli's semi-annual Warehouse Sale at the Burnaby Scandinavian Community Centre. All proceeds from this 2-day Warehouse Sale will be donated to the Looking Glass Foundation. Get a jump on your holiday shopping, and support a local business and LGF while you're at it!

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][printfriendly]

By Kaela Scott

Sometimes I think the longer I work in eating disorders the more I continue to be surprised by just how complicated out relationship with food, and therefore ourselves, really can be. There are so many different roles food plays in our lives and different ways in which we relate to food. Often when someone struggles with disordered eating or an eating disorder, they are blind to the different ways in which they engage with food that may be sabotaging them. Below are the 5 D’s of eating. Underneath all of these is usually an individual who has either long neglected their real need, or is more accustomed to being cruel to themselves than kind.

[dt_quote type="pullquote" layout="right" font_size="big" animation="none" size="18"]Underneath all of these is usually an individual who has either long neglected their real need, or is more accustomed to being cruel to themselves than kind. [/dt_quote]

Is there any one of these that stands out the most to you?

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[dt_divider style="thin" /]

Kaela Scott is a Registered Clinical Counsellor who specializes in Eating Disorders. She runs her own private practice and works with the Looking Glass Foundation in both their summer camp and their Hand In Hand Program. She has been passionate about working with eating disorders since freeing herself from her own struggle and realizing what it is like to be happy and well. When she isn’t working, you can find Kaela either cozying up with a cup of tea and her friends or up in the mountains going for a hike.

Kaela Scott is a Registered Clinical Counsellor who specializes in Eating Disorders. She runs her own private practice and works with the Looking Glass Foundation in both their summer camp and their Hand In Hand Program. She has been passionate about working with eating disorders since freeing herself from her own struggle and realizing what it is like to be happy and well. When she isn’t working, you can find Kaela either cozying up with a cup of tea and her friends or up in the mountains going for a hike.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

By Katalina Stephens

Whether you love it, loathe it, or prefer to lay low through it, Hallowe'en is here in all its grotesque glory! For many of us, this is a really fun time of year when we can get outside of ourselves, be playful with creative costume ideas, and connect with our inner kid (or the actual kids in our lives) by diving into spooky crafts and pumpkin-carving adventures. For a lot of people, though, it can be challenging to reconcile the fun, celebratory side of Hallowe'en with the potentially triggering presence of hyper-sexualized costumes, violent or gory themes, and of course the ubiquitous candy consumption.

When I was insecure in my own eating disorder recovery, I took solace in connecting with the roots of Hallowe'en and contemplating its spiritual origins. Traditionally called Samhain, a term which loosely refers to the end of the summer season, Hallowe'en comes from ancient Celtic pagan beliefs and traditions. It was the night when the metaphorical veil between the living human world and the unseen realm of the supernatural was at its thinnest – allowing all manner of spirits and unearthly creatures to walk among us. Jack-o-lanterns were carved from turnips, and they lit a path to hallowed crossroads, guiding all the lost souls to a place where they could safely cross over to the next world. People dressed as witches, goblins, ghosts, and demons so that they would blend in and go unnoticed by the legions of beings that might want to play some tricks on an unsuspecting human, and households left out offerings of sweet treats to placate the passing creatures. To me, it’s fascinating to look at the origins of all these Hallowe’en traditions, and see how they have persisted despite centuries of social and political change.

When I was insecure in my own eating disorder recovery, I took solace in connecting with the roots of Hallowe'en and contemplating its spiritual origins. Traditionally called Samhain, a term which loosely refers to the end of the summer season, Hallowe'en comes from ancient Celtic pagan beliefs and traditions. It was the night when the metaphorical veil between the living human world and the unseen realm of the supernatural was at its thinnest – allowing all manner of spirits and unearthly creatures to walk among us. Jack-o-lanterns were carved from turnips, and they lit a path to hallowed crossroads, guiding all the lost souls to a place where they could safely cross over to the next world. People dressed as witches, goblins, ghosts, and demons so that they would blend in and go unnoticed by the legions of beings that might want to play some tricks on an unsuspecting human, and households left out offerings of sweet treats to placate the passing creatures. To me, it’s fascinating to look at the origins of all these Hallowe’en traditions, and see how they have persisted despite centuries of social and political change.

I personally love Hallowe'en – not just because I love all things supernatural and fantastical, but also because it pulls focus toward a more spiritual element of the holiday: remembering and honouring the souls of those we've loved and lost, and wishing them safe passage into the unknown beyond our world. When we hit "pause" on all the clichés and trends associated with the season, it's much easier to breathe through the costumes, crowds, and candy to find something a little deeper and more meaningful.

[dt_quote type="pullquote" layout="right" font_size="big" animation="none" size="1"]Once you can identify your own personal Hallowe’en triggers, it will become much easier to come up with healthy self-care practices that will alleviate their effects when you encounter them, like using meditative mantras, plugging into your music, or talking to a friend.[/dt_quote]

Not everyone will feel the same way as I do, of course, and it's important to plan ahead and be mindful of your own triggers as you approach Hallowe'en 2018. Pay close attention to your self-care needs, and adjust your routine if you need to. It’s also very important that you take some time and space to reflect on the things that trigger you around Hallowe’en. Is it the overtly sexy costumes, candy and treat marketing, gore/violence, crowds, past negative experiences, fireworks, or maybe something else? Once you can identify your own personal Hallowe’en triggers, it will become much easier to come up with healthy self-care practices that will alleviate their effects when you encounter them, like using meditative mantras, plugging into your music, or talking to a friend.

Here are some additional tricks & treats to keep in mind as you walk with the ghosts and goblins this season:

Remember that this season, just like any other, is not explicitly out to “get” you. Everyone will enjoy Hallowe’en in their own way, and one of the healthiest mindsets we can have is to understand that nobody else’s costume choice, candy consumption, or theme party invitation is intentionally designed to upset you. And for those of us who just plain love to get into the Hallowe’en spirit, we can all try to be mindful of not putting accidental pressure on our friends to get as excited as we are. If you have a friend who just doesn’t dig Hallowe’en, try to meet them on their level and offer some support and understanding.

Remember that this season, just like any other, is not explicitly out to “get” you. Everyone will enjoy Hallowe’en in their own way, and one of the healthiest mindsets we can have is to understand that nobody else’s costume choice, candy consumption, or theme party invitation is intentionally designed to upset you. And for those of us who just plain love to get into the Hallowe’en spirit, we can all try to be mindful of not putting accidental pressure on our friends to get as excited as we are. If you have a friend who just doesn’t dig Hallowe’en, try to meet them on their level and offer some support and understanding.

From all of us at Looking Glass, we wish you a fun, safe, and spook-tacular Hallowe’en!

Katalina is the Volunteer & Program Manager at the Looking Glass Foundation, and holds a degree in Psychology from Simon Fraser University. She loves live music, theatre, writing, and singing when no one is listening.

By Kaela Scott

Q: I spend a lot of my time in isolation because of my eating disorder. My goal for myself this year was to try to spend a bit more time with those I love but whenever I get asked I automatically want to say no. How can I challenge myself to spend more time with my friends while still feeling safe?

A: I get asked different versions of this question a lot in my practice and in my work at the Looking Glass Foundation. We know that eating disorders thrive in isolation and the more time you spend with your eating disorder, the less time you have to authentically connect with those who lift your spirits. It typically doesn’t feel easy stepping outside of our routines and doing something different. My natural inclination a lot of times is to say no to unexpected invites because I am both a creature of habit and a creature of comfort. What I have realized however, is that almost every time I say yes, I am grateful for it and typically have a better time than I expected. As we enter into Fall and the beginning of the slower months, now is a great time to reflect on the types of connections that make us feel fulfilled and then look at how to create more space for them in our lives. We know that recovery doesn’t happen if we don’t make a concerted effort. What effort do you feel you need to make to enhance the connections you have with the people you love?

There are lots of different ways that you can do this on your own terms. For example, you mention that it is always your friends asking you to join them on their planned activities. Maybe instead of waiting to be invited, you could be the person to invite them to do something that falls within your comfort zone. Another option would be to create some awareness around the activities that feel manageable for you, like going for tea or hanging out at peoples’ homes. Or alternatively, if going out to eat is one of your goals, pick a meal and a friend that will be supportive of your recovery. Saying yes to the things you know underneath you want to do will make you feel more confident about choosing to say yes to certain invites. Finding your own balance is important because it allows you to maintain a focus on recovery without feeling so overwhelmed that recovery doesn’t feel worth it.

I think one of the beautiful but also challenging parts of recovery is learning to step outside of your comfort zone into things that you know are good for you.

![]()

I think one of the beautiful but also challenging parts of recovery is learning to step outside of your comfort zone into things that you know are good for you. In my practice, I always tell my clients that it is important that they challenge themselves to do things that are uncomfortable but not intolerable. As with most things in recovery, what is uncomfortable for some is intolerable for others and vice versa. The journey to wellness is going to be uncomfortable – in many ways it has to be if we want to make a significant and permanent change. I think what is important is that you look at how you can be uncomfortable and safe at the same time. Your friends love you and want to help you live a happy, fulfilling life. Spending time with them, while different, will likely make you feel more motivated to have a life outside of your eating disorder. Sometimes we need recovery reminders when we are struggling because otherwise, left alone with our disorder, we simply focus on the reasons why recovery is hard instead of reasons why it’s worth it.

I think one of the beautiful but also challenging parts of recovery is learning to step outside of your comfort zone into things that you know are good for you. In my practice, I always tell my clients that it is important that they challenge themselves to do things that are uncomfortable but not intolerable. As with most things in recovery, what is uncomfortable for some is intolerable for others and vice versa. The journey to wellness is going to be uncomfortable – in many ways it has to be if we want to make a significant and permanent change. I think what is important is that you look at how you can be uncomfortable and safe at the same time. Your friends love you and want to help you live a happy, fulfilling life. Spending time with them, while different, will likely make you feel more motivated to have a life outside of your eating disorder. Sometimes we need recovery reminders when we are struggling because otherwise, left alone with our disorder, we simply focus on the reasons why recovery is hard instead of reasons why it’s worth it.

Take some time and see what goals you really want to set and follow through on with regards to connecting with loved ones. Know that its normal and okay to be overwhelmed but challenge yourself to get out of that place and act on your healthy hopes and longings. If you ever need a bit more support, know that we are always only a phone call away and would be happy to connect.

Kaela Scott is a Registered Clinical Counsellor who specializes in Eating Disorders. She runs her own private practice and works with the Looking Glass Foundation in both their summer camp and their Hand In Hand Program. She has been passionate about working with eating disorders since freeing herself from her own struggle and realizing what it is like to be happy and well. When she isn’t working, you can find Kaela either cozying up with a cup of tea and her friends or up in the mountains going for a hike.

Kaela Scott is a Registered Clinical Counsellor who specializes in Eating Disorders. She runs her own private practice and works with the Looking Glass Foundation in both their summer camp and their Hand In Hand Program. She has been passionate about working with eating disorders since freeing herself from her own struggle and realizing what it is like to be happy and well. When she isn’t working, you can find Kaela either cozying up with a cup of tea and her friends or up in the mountains going for a hike.

By Jasmine C.

“Radical acceptance rests on letting go the illusion of control and a willingness to notice and accept things as they are right now, without judging.” — Marsha Linehan

Radical acceptance – a component of dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT), created by Dr. Marsha Linehan in the 1980s, and a essential tool in my recovery. While DBT has been most widely studied as a treatment for borderline personality disorder, it has also shown promise in the treatment of eating disorders. Interestingly, it emerged from the mind of a woman who spent her adolescence in a psychiatric hospital, and spent much of her early life battling severe mental illness. Regardless of its origin, however, radical acceptance can stand alone as a valuable skill when faced with life’s challenges.

I was first introduced to radical acceptance during a particularly difficult inpatient stay a few years ago. To say that things had gotten bad would be an understatement, and I had more or less given up on the prospect of recovery. I was entirely consumed by the eating disorder. I saw no way out, no life beyond it. My psychiatrist admitted me as an involuntary patient, and so I was forced, internally kicking and screaming, into the hospital.

With my control having been ripped from my unwilling grasp, my initial reaction was to fight to get it back. I refused to comply with the program, I made my distaste for it very clear, and I spent hours plotting my escape. Obviously, this didn’t work. The weeks kept going by, and I was still stuck in the hospital. Meanwhile, I would often hear the nurses and other patients talk about practicing “radical acceptance”, and I gradually came to understand what they meant. Recognizing that some things in life cannot be controlled. Acknowledging that pain is inevitable, but it does pass. Letting go, in the style of Elsa.

Recognizing that some things in life cannot be controlled. Acknowledging that pain is inevitable, but it does pass. Letting go, in the style of Elsa.

Eventually I started to realize that my fighting wasn’t doing anything to change my situation, but was rather making me stressed and miserable, and alienating me from my doctors, nurses, and fellow inpatients. So I decided to try accepting my situation instead. I finished all my meals, went to all the groups, made friends with the other patients, and set my eyes on recovery. It was liberating. A few weeks later, I was made a voluntary patient and was offered the choice of leaving, but I actually chose to stay.

The word “radical” comes from the Latin “radic”, meaning root, and thus radical acceptance refers to a complete, fundamental acceptance of a situation from its root. However, to me it also reflects the other meaning of the word “radical”, the independence of or departure from tradition; innovative or unorthodox. In many ways deciding to stop fighting felt less like “giving up” and more like leaping off a precipice into the unknown and frightening. The freedom it offers is thrilling.

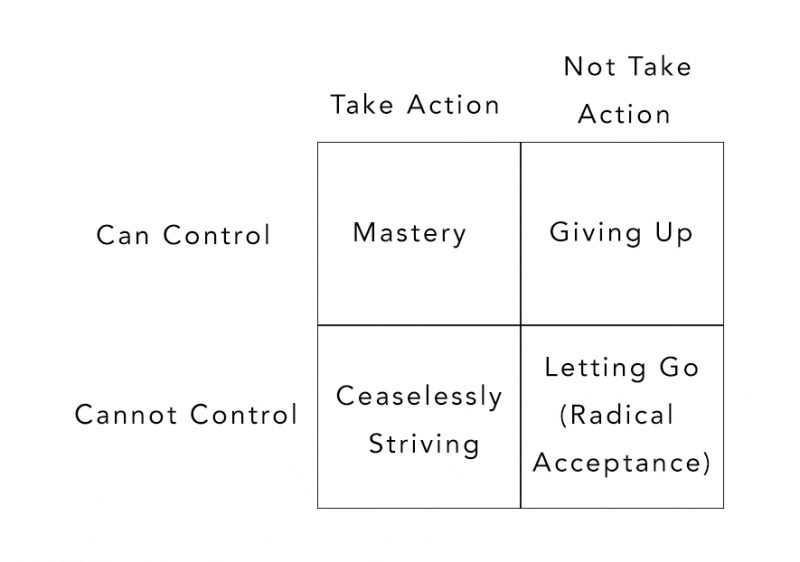

Radical acceptance has also been explained to me in terms of the “personal power grid”:

In a situation you do have control over, taking action can lead to mastery – solving the problem, making things exactly as you want them. In a situation you do not have control over, it will lead instead to “ceaseless striving”, a category I often find myself in. In these situations it is often healthier to not take action, to let go, to accept. Being involuntarily confined to a locked psychiatric unit is an extreme example of a situation in which one does not have control, but this idea applies equally well to many of the painful situations one might encounter.

People with eating disorders are known for our tendency to try and control ourselves and our lives to excess. We have a pathological need to control that often leads to self-destruction. We “ceaselessly strive” to the point of utter exhaustion. And so an integral part of our recovery is learning how to radically accept instead. Rather than judging our bodies as “bad” and trying to change them, the thing to do is accept our bodies as they are. Beyond that, we can use radical acceptance to deal with life’s bigger concerns, the ones we try to cope with by burying ourselves in our eating disorders. It’s easy to get carried away with anxiety, judgments and the racket in your head, but if you take a moment to look at things as they really are, and radically accept that reality, you’ll stumble into an unexpected freedom and peace.

Jasmine is a neuroscience student at the University of British Columbia, and is fascinated by the interaction between mental and physical health. Some of her favourite things include mountains, tea, and her dog, Ollie.

By Gretchen Cohen (Jumo Health) in collaboration with the Looking Glass Foundation

As the summer passes into a fresh school year, we often see some anxiety associated with changes in schedule beginning to manifest among students – especially those who experience eating disorders or body image issues. If you are a parent or caregiver of a student who faces these challenges, this blog entry may be a helpful resource as you find your footing in the first few weeks of school.

Like many other mental health concerns, people who struggle with disordered eating may find solace in their routines. It is important to strive for balance and flexibility within routine, however, so that we can make room for the unexpected and allow space for spontaneity. It may be useful to think of your routine in terms of “structured flexibility,” rather than a rigid set of rules and expectations. Although the beginning of the new school year is far from unstructured, returning to that specific routine after months of living out a summer schedule can be difficult, and even upsetting, for your child.

No matter the type of disordered eating they cope with, the commonly associated mental health concerns can become overwhelming as your child adapts to the new routine. Here are some helpful ways to support your child’s back-to-school transition.

Prepare through dialogue![]()

Eating disorders are complex conditions that often consume the majority of a person’s thoughts in any given day. Initiating a conversation about their mental health and how it may be impacted by the school environment will encourage mindfulness throughout the coming weeks. Have a discussion about this as soon as you can to gently bring their awareness to the changes associated with the school year. Once engaged, begin to delve into their feelings about this change and work towards discovering what your child wishes could be done about these new disruptions. Even if what they want is unrealistic (i.e.: cancel school forever), it is important for you to allow them to be heard and understood. This will also give you a good starting point for exploring some compromises and ideas of what they actually can control or change about the situation.

Prepare through practice

By starting the conversation about your child’s mental health at the beginning of the school year, you’ll give your family the opportunity to discuss the changes in real time as you experience them. You will be helping to alleviate your child’s anxiety simply by talking it through, and preventing them from spiraling into negative thought patterns where they constantly imagine all of the negative consequences that might happen as a result of the changes around them. It will also be very helpful if you encourage them to identify the areas of their schedule or their school environment that cause them discomfort – in other words, have them identify their triggers. Use this information to develop specific, positive coping strategies with your child that they can use when they find themselves feeling triggered, and help them to practice these strategies at home so that when they are caught in a moment of high anxiety, they can recall the info more easily. Your child may be experiencing a lot of stress at being unable to schedule each day around their disordered thoughts and behaviours, and by familiarizing your child with these flexible coping strategies, you will teach them they can learn to trust themselves instead of the eating disorder.

Recruit support for your child

As a parent, you have a far greater understanding of your child’s unique experience and challenges than most other people in their lives. Once they have returned to school, of course, it is a lot harder for you to be the one reading and responding to their behavioural cues. Consider reaching out to some of the key people in their lives – teachers, coaches, or counsellors, for example – to let them know about your child’s eating disorder triggers and the ways in which their moods and behaviours can be affected. Do this only if it feels appropriate and helpful, and be sure to stress the importance of keeping your child’s situation confidential.

The intent here is not to offload responsibility for your child’s emotional regulation onto other adults, but to bring awareness and context around potentially difficult situations so that their behavior isn’t misinterpreted. Ultimately, the goal is always to empower your child with the right self-regulation tools and resources (like mindfulness, meditation, breathing, etc.) so that they can guide themselves through triggers and challenges, but it can be helpful to have the mentors in their lives on hand to remind them that maybe this would be a good time to take a mindful moment. Having this line of communication open may in turn lead to new information for you about resources your child can use at school (like designated quiet zones, mental health clubs, or buddy programs), which can help to reinforce the supports already available to your family.

![]()

Recruit support for yourself

It’s not all about your kid! For parents, it can be way too easy to lose track of all sense of self when their family’s wellbeing and happiness are at the forefront of life’s priorities. And it can actually feel like good parenting – you’re embodying the utterly selfless, domestically competent, ‘I’ll-sleep-when-you’re-thirty’ kind of parenting you see on the Instagram pages of supermoms. You are #parenting goals and you’re nailing it.

This, however, is a trap. Putting others before yourself all the time leads you down exactly one path: Burnout. It’s not sustainable, it’s not healthy, and it’s not even good parenting. If your best friend came to you for advice, would you tell them that the meaning of life is to ignore their own health and wellbeing, sacrificing everything they have to give of themselves for the benefit of others? No? Then let’s be sure you’re not holding yourself to this absurd expectation, either. Reach out for support – have friends, colleagues, counselors, etc., whom you can talk to. Set aside time to do the things that make you feel grounded, renewed, and happy – things that make you feel like you. You’ll be way better equipped to navigate the stressors of supporting your child’s recovery, and you’ll also be giving them a great role model for self-care by actually walking the walk.

Take it week by week

Take time to check in with your child about the strategies you’ve created together. Eating disorders exist in an ever-changing form, and what may have worked for your child a month ago no longer provides the same benefit it once did. Having regular check-ins will allow you to stay in touch with your child’s emotions and the day-to day experience of their disorder, and together you can make appropriate adjustments to their coping strategies in response to any new challenges that come up.

Coping with a complex mental health concern like an eating disorder is not an easy feat - but it is possible. The feelings and perceptions experienced by someone struggling with disordered eating may not always be easy to understand for those looking in from the outside, but consistent patience, listening, and open communication in the coping process can help to uncover common ground. A little preparation, and a lot of structured flexibility, can go a long way in helping to relieve your child’s anxiety around school-related changes and uncertainty.

The Looking Glass Foundation is a caring community that offers support to those affected by eating disorders including loved ones. In addition to helping with prevention and early intervention, we offer innovative programs for eating disorder support, recovery, and sustained relapse prevention. We are about getting to the other side of eating disorders, to eventually achieving a world without this devastating disease.

The Looking Glass Foundation is a caring community that offers support to those affected by eating disorders including loved ones. In addition to helping with prevention and early intervention, we offer innovative programs for eating disorder support, recovery, and sustained relapse prevention. We are about getting to the other side of eating disorders, to eventually achieving a world without this devastating disease.

By Kaela Scott

Q: This change of seasons often feels really overwhelming for me. As soon as I adjust to my life and my recovery process in one season, the next season is here and recovery feels different and harder all over again. What should my focus be now that we’ve moved into Fall?

A: This is such a great topic because without a doubt we are impacted by the change in seasons and the messages each season seems to bring. Before I jump in to answer your question, I just want to acknowledge that it is really normal to feel overwhelmed by season changes and that even people without an eating disorder can feel the effects of season transitions. Because each season is unique, each one can make us feel different physically and emotionally. Be kind to yourself in your overwhelm and try to take a moment to breathe so you can remind yourself that you don’t have be anywhere other than where you are right now.

My favorite season of the year by far is Fall. I find the cooler and shorter days not only comforting but they also seem to give me greater permission to slow down and take care of myself after the busy rush of summer. I think this is one of the greatest things about living in a place where there are seasons – each season brings its own gift and focus. Fall for me has always felt like a transition time. For many years, it was the time when I went back to school and I don’t think I have ever lost the feeling of September feeling like the start of the year. Now that we have jumped into Fall, I think it is important to look at how it may be a time of transition for you as well, and the transitions that I want you to prepare yourself for, along with spending time reflecting on the transitions you want for yourself.

Fall is a warming season. It is a time where we pull out our scarves and boots, and hot drinks can feel like a necessity all day long instead of just in the morning. Along with warmer clothing, it is also a season where our bodies will naturally crave warming foods. This is normal and incredibly healthy. Our bodies ask for more soups, stews and foods with warming spices like cinnamon; crisp fruits and veggies get replaced with roasted veggies, and oatmeal can feel more comforting than a smoothie first thing in the morning. For some this may be easy, but I also know for many people struggling with an eating disorder, it can be difficult to listen to what your body is asking for and feel like it is safe to respond to its requests. It is healthy and important to try to tap into our bodies needs for these types of foods. Just like we wouldn’t deny ourselves a cozy sweater when we are cold, we don’t want to deny what it is asking for nutritionally as well.

As the rain sets in and weeknight get-togethers at the beach are more of a distant memory, use your time to nourish yourself as a whole person and to remind yourself that you matter.

Along with our body’s needs changing around food and warmth, I think Fall is also a time when our heart’s needs change as well. Summer is often a season of do-ing and busyness. Most people slide into fall feeling disconnected from their self-care and in need for a reset. As the days become shorter and the weather becomes cooler, I think it gives us an opportunity to reconnect with the forms of self-care that are focused on slowing down and being present. It is a time when sitting with a cup of tea feels restorative instead of out of place with the world around you, and a time when taking a bath while reading a book leaves you feeling warm and relaxed instead of hot and uncomfortable. Whatever your preferred types of self-care may be, pay attention to the ones that feel soothing for you right now and find a way to make them more of a priority. As the rain sets in and weeknight get-togethers at the beach are more of a distant memory, use your time to nourish yourself as a whole person and to remind yourself that you matter.

Autumn gives us an opportunity to transition into a different focus. I think there is no better time than now to make that focus recovery centered in whatever way that means for you. Maybe it is learning to lean into your self-care practice with more intention, or allowing your body to rest when it is asking for it. Perhaps it is creating the space for your body to turn to more warming foods to go alongside your favorite cozy sweaters. Whatever it might be for you, give yourself the space to honor the transition that this season brings and to welcome its gifts with open arms.

Kaela Scott is a Registered Clinical Counsellor who specializes in Eating Disorders. She runs her own private practice and works with the Looking Glass Foundation in both their summer camp and their Hand In Hand Program. She has been passionate about working with eating disorders since freeing herself from her own struggle and realizing what it is like to be happy and well. When she isn’t working, you can find Kaela either cozying up with a cup of tea and her friends or up in the mountains going for a hike.

Kaela Scott is a Registered Clinical Counsellor who specializes in Eating Disorders. She runs her own private practice and works with the Looking Glass Foundation in both their summer camp and their Hand In Hand Program. She has been passionate about working with eating disorders since freeing herself from her own struggle and realizing what it is like to be happy and well. When she isn’t working, you can find Kaela either cozying up with a cup of tea and her friends or up in the mountains going for a hike.

By Sarah Rzemieniak

My eating disorder recovery journey was anything but linear, as I’m sure so many of you can relate to. There were so many steps forward, slips backward, plateaus and relapses.

When I look back on my journey though, one thing that stands out for me as being so helpful was focusing ahead only as far as I could visualize. I would then take steps forward that weren’t so small that they barely challenged me and weren’t so big that I felt overwhelmed to the point of thinking I should give up. For me, this made such a difference in my recovery.

Aiming for ‘recovered’ did not happen for me until much later in my journey, even though I knew it was possible and had seen many others who were recovered. What I hoped for during most of my recovery journey was a bit more freedom, a bit less exhaustion, a bit more of a life - but not too much, not at first.

Throughout my recovery my ambivalence was so ever-present, as was my doubt that I could ever be fully recovered. I felt confused about what ‘recovered’ even meant for me, and so it felt very hard to make ‘recovered’ my day-to-day commitment.

However, what I often could do was commit to taking challenging yet doable steps, one at a time to make life just a bit better, a bit less rigid, and a bit more free. Over time, these steps added up and I felt ready for so much more.

It reminded me of what Carolyn Costin and Gwen Schubert Grabb describe in their book 8 Keys to Recovery from an Eating Disorder. These small, gradual steps brought forward my inner Healthy Self and gave it a taste of being in control in a way that didn’t cause too much resistance or a desire to give up. These repeated small steps gave me the desire to set bigger goals, until my goal finally became, “I want to be fully recovered.”

Everyone’s recovery journey is unique, and what constitutes manageable steps will be completely different for everyone. For some, the desire to become fully recovered will feel right from the start. For others, it may take some time. Furthermore, if your immediate health requires it, large steps may be required of you, before you truly feel ready for them. Each of our journeys is so unique, yet similar in so many ways.

The most important thing is to never give up hope that things can get better and change in surprising ways with enough time and gradual steps along the way. And to also remember that slips back, plateaus and relapses are the rule, not the exception, on the recovery journey. Reach out for support from those who make you feel safe and cared for, as hard as this can be. Read stories and meet people who have recovered - it’s amazing what can resonate and inspire hope.

Each of our mountains is unique, and each of our journeys has different and beautiful wonders, lessons and opportunities for growth along the way.

Often, my recovery journey felt like climbing a forested, misty mountain full of challenges to overcome. I couldn’t clearly see the summit until I was very close to it, and so I just took the journey one switchback at a time. However, with each switchback solidly behind me, life was that much more free and hopeful, until finally the summit was in my sight, and then there. Each of our mountains is unique, and each of our journeys has different and beautiful wonders, lessons and opportunities for growth along the way.

Often, my recovery journey felt like climbing a forested, misty mountain full of challenges to overcome. I couldn’t clearly see the summit until I was very close to it, and so I just took the journey one switchback at a time. However, with each switchback solidly behind me, life was that much more free and hopeful, until finally the summit was in my sight, and then there. Each of our mountains is unique, and each of our journeys has different and beautiful wonders, lessons and opportunities for growth along the way.

If you can’t see the summit, try your best to not give up, and don’t feel bad if aiming for the summit feels like an unrealistic or unfathomable goal right now. It doesn’t mean you won’t make it there. Focus on where you are now, and on the next challenging but manageable step you feel ready to take. Small steps and gradual changes truly do add up over time.

If you wish to explore some thoughts around taking one step at a time in your recovery, try these journaling prompts:

Sarah is an eating disorder recovery coach certified through The Carolyn Costin Institute, and runs her own private practice in Victoria, BC and online worldwide. She has had a passion for helping others to recover from eating disorders and disordered eating since going through her own recovery journey and realizing what a transformative journey it can be. In her free time Sarah loves to travel, walk near the ocean, knit, and drink herbal tea curled up with a good book.

Interview with Kaela Scott

We sat down with LGF's very own ED therapist, Kaela Scott, to answer some common questions about our wonderful peer support program, Hand in Hand. Kaela spearheaded this program two and a half years ago and since then, with the help of the LGF team, has facilitated over a hundred matches between inspiring participants and amazing volunteers - some of which have been matched from the very beginning!

As a Therapist, what makes you so excited about this program?

I have the incredible benefit of working for Looking Glass while also running a private practice. What this means is that I see first hand the kind ofsupport people are looking for out in the community. Often those who struggle feel like they don’t have someone they can talk to about what they are experiencing. Our Hand in Hand program, I believe, has changed how people can receive support that is recovery focused without it being treatment. It meets people where they are at emotionally in their recovery, which is unique because readiness is not a factor for receiving support. Very rarely do we have an opportunity to develop a relationship with someone who cares about our overall wellbeing and who is there to provide support without other expectations or conditions. After two and a half years I can confidently say that Hand in Hand is creating a change in the Eating Disorder support community one connection at a time.

After two and a half years I can confidently say that Hand in Hand is creating a change in the Eating Disorder support community one connection at a time.

What are the limitations of the program that may prevent people from participating?

One of the sad experiences many of our participants have faced is reaching out for help only to find out that so many programs either tell them they are too sick or not sick enough to participate. At the Looking Glass, we do our best to have as few limitations as possible. Currently for our program participants need to be 14 years and older. In addition, we require that people be medically and psychiatrically stable. What this implies is that a participant can’t currently be hospitalized or require hospitalization for their disorder or any other psychiatric condition. Hand in Hand is run by volunteers and ensuring that everyone is safe while they are connecting is mandatory.

What are the greatest strengths you have noticed about this program now that it has been running for almost 3 years?

There are many but I will go with my top 3:

Is there anything you wish this program provided that it doesn’t currently?

I am really proud of the program and the support it provides to the eating disorder community but one area I would like to see us grow into is groups. There is a really high demand for group sessions and it is something we are very aware of at the Foundation. My hope is that at some point we will be able to offer that to our community.

As a participant, how long can I stay in this program?

This is one of the most special things about Hand in Hand. At Looking Glass we understand that eating disorders don’t have a predictable recovery date and that support needs are different at various stages of the recovery process. While volunteers are asked to commit to a minimum of 6 months from the start of a match, participants can take part in the program for as long as they want. We have many original matches who have been connected for the entire duration of the program, and other participants who have been matched with more than one volunteer.

Seeing as the Foundation is based in Vancouver, do you have to live in Vancouver in order to volunteer or participate in the program?

Not at all. That’s one of the things that is so great about this program is that you can live anywhere in the country and participate, thanks to Skype. The only limitation for volunteers is that they have to take the training in person, which for the foreseeable future only takes place in Vancouver. Many of our volunteers have moved and live all over the country and are matched in their current city either in person or over Skype.

How much knowledge or experience of eating disorders do volunteers need to have in order to become Hand in Hand Peer Supporters?

The only thing we expect from our volunteers is that they have a genuine interest in supporting this population. While many of our volunteers have a personal history of an eating disorder, it isn’t expected or required.

As a volunteer, what kind of training can I expect before being matched in the program?

Volunteers are trained over a 2 day weekend using a combination of theory, discussion and role play to help develop their skills and knowledge. From my experience, teaching using all of these modalities sets the volunteers up to feel confident supporting someone who is struggling with an eating disorder.

Is this program free?

It is! The only costs associated with the program are the beverages participants may choose to purchase if they go for coffee with their match.

If you'd like to read more or sign up as a participant visit here.

If you'd like to volunteer, you can sign up here.

Kaela Scott is a Registered Clinical Counsellor who specializes in Eating Disorders. She runs her own private practice and works with the Looking Glass Foundation in both their summer camp and their Hand In Hand Program. She has been passionate about working with eating disorders since freeing herself from her own struggle and realizing what it is like to be happy and well. When she isn’t working, you can find Kaela either cozying up with a cup of tea and her friends or up in the mountains going for a hike.

Kaela Scott is a Registered Clinical Counsellor who specializes in Eating Disorders. She runs her own private practice and works with the Looking Glass Foundation in both their summer camp and their Hand In Hand Program. She has been passionate about working with eating disorders since freeing herself from her own struggle and realizing what it is like to be happy and well. When she isn’t working, you can find Kaela either cozying up with a cup of tea and her friends or up in the mountains going for a hike.

By Emily Gaudette

*Trigger warning: This article makes general references to sexual harassment. Please read with caution.

I was always a bit of a late bloomer. I got my period when I was fourteen. I had my first kiss at eighteen. When I was 12, I remember my mom holding back laughter when she bought me my first bra – a double A. It wasn’t just any AA, as most were too large. My mother, who despite my protests insisted in partaking in this mortifying experience with me, liberally and loudly explained the situation to The Gap’s finest Sales Associate. While I fought the idea of diving into a pile of clothes and disappearing, the sales associate directed my mom and me to the bras that generally fit smaller. I still had to stuff it for a while.

I remember being equally terrified that someone at school might find out that I folded toilet paper inside my new beige lingerie every morning and elated that I could finally be considered a woman. In my tween brain, this was the only milestone I could force, the only propellant into what I thought adulthood consisted of that I could control. I couldn’t force my period into existence, but dammit, I could wear a bra. And hopefully the “when are you going to get your period?” and “are you finally a woman yet?” questions and giggles at my child body from people with only slightly less childlike bodies would cease. No longer would I be the only girl in my group of friends whose bra was not snapped doing laps in gym class. No longer would I be the only girl whose breasts had no safety against the inevitable, protested, always unasked-for groping by the boys at school.

I remember being equally terrified that someone at school might find out that I folded toilet paper inside my new beige lingerie every morning and elated that I could finally be considered a woman. In my tween brain, this was the only milestone I could force, the only propellant into what I thought adulthood consisted of that I could control. I couldn’t force my period into existence, but dammit, I could wear a bra. And hopefully the “when are you going to get your period?” and “are you finally a woman yet?” questions and giggles at my child body from people with only slightly less childlike bodies would cease. No longer would I be the only girl in my group of friends whose bra was not snapped doing laps in gym class. No longer would I be the only girl whose breasts had no safety against the inevitable, protested, always unasked-for groping by the boys at school.

To be clear, I did not want boys to snap my bra in gym class, but I was ostracised because I didn’t have a bra to snap. And if a boy snapped your bra as you ran past him in gym class, it meant he liked you. And having a boy like you was a sure-fire way to get people to talk to you, perhaps even look up to you. Each time my bra was snapped, I guess I thought the Popularity Gods put one more notch on my popularity belt. I wanted to be popular. I also made it very clear that I did not want to be groped by them, but it happened with or without a bra, and especially with the added layer of toilet paper between me and their hands, with a bra was safer – their sweaty, adolescent fingers further away.

I mention these snippets of memories, delicately folded into my subconscious like toilet paper in a twelve-year-old’s bra, because these formative years describe my first experiences of hating my body. More than that, these are some of the first experiences I had in becoming aware of my body – the length of my arms, the size of my thighs, the colour of my skin (ivory, as my first foundation informed me) – and that how “society” thinks you look in your body could determine your value. I became thoroughly acquainted with the idea that a girl’s body is different than a boy’s in all the ways that Sex-Ed failed to mention. When the boys in class asked me to put my legs together to see if I had a thigh gap, I learned that a girl’s body must always be ready for scrutiny. When they determined that there was a barely acceptable space between my thighs, I was relieved in spite of myself.

These early years shaped my relationship with my body. It wasn’t only these experiences. It was also my internalization of the metrics that magazines and casting directors used for measuring a woman’s ability, skill and importance. It was my friend drinking only V8 at lunch to lose weight in fifth grade. It was photoshopped pictures of already gorgeous women. It was my mom calling me beautiful and my friends complimenting my blue eyeshadow. It has taken me a long time to realize how this obsessive emphasis on appearance affected my body image -- and how my poor body image was the crevice in my psyche that allowed my eating disorder to develop.

These early years shaped my relationship with my body. It wasn’t only these experiences. It was also my internalization of the metrics that magazines and casting directors used for measuring a woman’s ability, skill and importance. It was my friend drinking only V8 at lunch to lose weight in fifth grade. It was photoshopped pictures of already gorgeous women. It was my mom calling me beautiful and my friends complimenting my blue eyeshadow. It has taken me a long time to realize how this obsessive emphasis on appearance affected my body image -- and how my poor body image was the crevice in my psyche that allowed my eating disorder to develop.

I recognize that these memories don’t hold a candle to the stories of far too many other women. The bullying I encountered felt almost good-natured compared to the bullying that those same people inflicted on others in my class. The sexual assault I experienced was a mere inappropriate groping, touching, kissing. Yet it was enough to destroy my self-worth and body image. It was enough to directly or indirectly contribute to the eating disorder I’ve lived inside for six years. I will not minimize my experience because it is a common and normalized one or because others experience much worse. All of it is wrong. All of it perpetuates diet and rape culture (which prop each other up, arms of the same beast). So, all of it must be brought to light.

After being sexualized, groped and teased about my body throughout elementary school, I sort of dissociated from it. My body no longer felt like home. I felt like a foreigner in it, the script on my rib cage in a different language. After my child body eventually died and I started growing into a woman’s body, I did so truly and completely. I discovered all the ways a girl could wish to not exist, or at least wish her stomach didn’t. I was no longer the thin, cute, small, petite girl for whom my mom bought a first bra. I grew. My face changed, my stomach rounded and, I should note, that my breasts grew to a sizable I-is-for-irony. Yes. I. A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, double I. A few years earlier, I was made fun of for “being flat”. Suddenly, it felt like a silence surrounded my body, like I was the elephant in the room (Puberty, man. What a ride.). This body wasn’t mine. I denied the reality of it; ignored my stomach, ignored my breasts, ignored seeing the letter “L” instead of “S” on clothes tags. This wasn’t my body. I was just growing, I thought. Soon, I’d finish growing and be small again. My mom told me you grow out before you grow up. I was just growing out and soon I’d grow taller and be small again.

I am a socialized product of my culture and I was obsessed with becoming thin and small, but I do remember a time before all of this in which my body was just the thing that got me from place to place. My body was not something to be remarked upon, it just was. There was no moralization of my body parts or of food. I never even thought about it. I remember being confused when friends recycled conversations about their distaste for their own body: how they hated their big thighs or never looked down because they thought they had a double chin. I remember being genuinely confused by their obsessive remarks about their bodies. I was immersed in diet culture, fat-phobia, and body-shaming practices long before I understood them. I was body neutral. I had a body that could do all the things I needed it to do. I had greasy hair that people mistakenly thought was great conditioner and I had lanky, uncoordinated limbs and two eyes, a nose, ten fingers. There were no moral implications to be made about my size or shape. I didn’t celebrate it, I just lived in it. Even as a child, I had more important things to worry about.

I am a socialized product of my culture and I was obsessed with becoming thin and small, but I do remember a time before all of this in which my body was just the thing that got me from place to place. My body was not something to be remarked upon, it just was. There was no moralization of my body parts or of food. I never even thought about it. I remember being confused when friends recycled conversations about their distaste for their own body: how they hated their big thighs or never looked down because they thought they had a double chin. I remember being genuinely confused by their obsessive remarks about their bodies. I was immersed in diet culture, fat-phobia, and body-shaming practices long before I understood them. I was body neutral. I had a body that could do all the things I needed it to do. I had greasy hair that people mistakenly thought was great conditioner and I had lanky, uncoordinated limbs and two eyes, a nose, ten fingers. There were no moral implications to be made about my size or shape. I didn’t celebrate it, I just lived in it. Even as a child, I had more important things to worry about.

These days, I strive to simply live in my body. These days, I have more important things to worry about. And it’s a damn good feeling.

I think about that child now and again. That space between my obsession with thinness and my confusion regarding others’ obsession with thinness allowed me to understand that there is another way to perceive the world. There is another way to live inside your body. Much like learning to eat intuitively and to destroy all the food moralizations I’ve built over the years, I’ve been learning to come back inside an intuitive relationship with my body and to destroy the body moralizations I’ve built over the years. I think these practices go hand in hand. When you think about how your body feels when eating a certain food, you must be inside your body to feel it. This is what I strive for these days. It’s a process. There are days when I hate my body like I once did and there are days where I dance naked in front of my mirror and smile at what jiggles. It is unrealistic to think I’ll ever be naïve to the culture I’m immersed in, which is fine. I should be all too aware. However, in writing this story I now remember a way of life that combats diet culture. My younger, body-neutral self can act as my mascot for the intuitive relationship with my body and food that I know I am capable of. These days, I strive to simply live in my body. These days, I have more important things to worry about. And it’s a damn good feeling.

Emily is a proud blog contributor for the LGF, an inevitably struggling student, an efficient consumer of Netflix content, a coffee addict and pursuer of ED recovery. She is also participating in many programs that LGF has to offer.